To celebrate the end of one tour, Shearwater from Austin, Texas, started another one. Believe it or not, they graced our wee town with a performance which might have spooked the band a little as the venue is in a WWII shelter bunker that is now a listed building and called the Musikbunker. I turned up already and shrieked my way through the dark bunker, ready or not for a Shearwater Interview. Anyhow, those who in spite of it being a weekday night and the footie being on came, were treated to a magnificent evening. The fabulous Emily and Dan alias Cross Record opened and had the present company entranced.

The following set of Shearwater was immaculate, the more astounding as Jonathan Meiburg is touring with a very young band whose first tour it was on the back of Shearwater’s album “Jetplane And Oxbow” of which there were many songs. There were trancey bits and psychy bits and rocky ones and poppy ones and they all shone. All of the band members (Lucas Oswald on guitar, Emily Lee on keys, Sadie Powers on bass and Josh Halpern on drums) contribute to the masterpiece and above all lingers Jonathan Meiburg’s guitarplgaying and that extraordinary voice which, if not before, persuades the last doubtful (if there were any) in the two encores which were Bowie covers from the album Lodger.

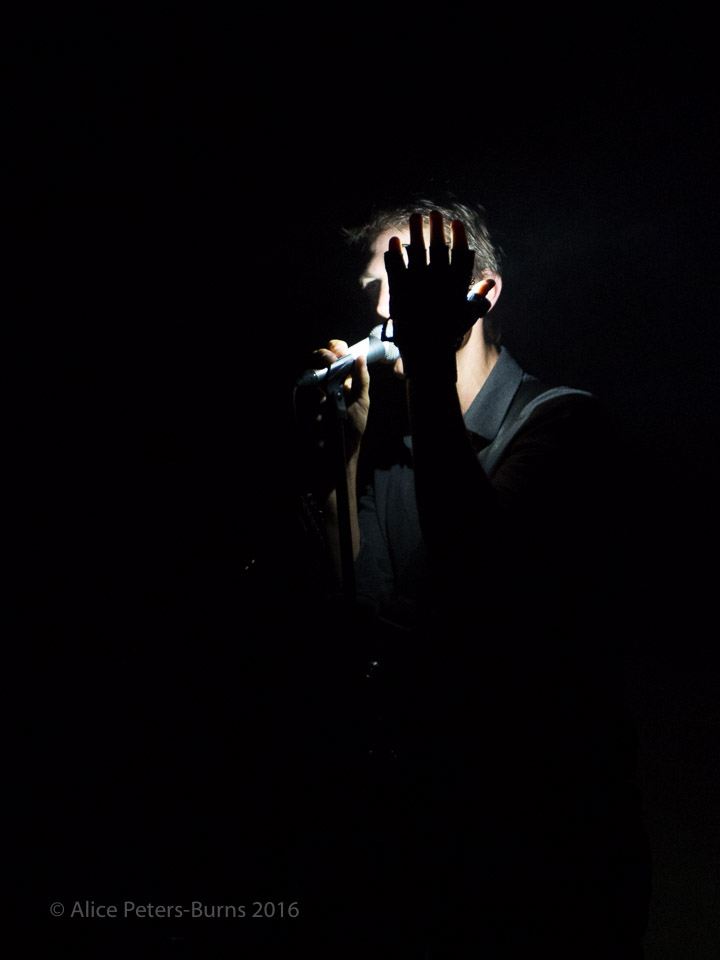

Bringing with them their own DIY but effective light show (oh my, that glove…), this set showed that the lastest album was also written with live performance in mind.

Jonathan Meiburg kindly gave me an interview before the show which you can read below. You can still catch them at the following places:

17 June: Le Port Franc* – Sion (CH)

18 June: Hana-Bi* – Ravenna (IT)

20 June: La Malscène* – Tavannes (CH)

22 June: InMusic Festival – Zagreb (HR)

23 June: Kino Siska* – Ljubljana (SI)

24 June: Kino Ebensee* – Ebensee (A)

26 June: A38 – Budapest (HU)

27 June: Arena – Vienna (A)

28 June: Strom – Munich (D)

29 June: Gleis 22 – Münster (D)

30 June: Vera – Groningen (NL)

01 July: Paard – The Hague (NL)

02 July: Conincx Pop Festival 2016 – Elsloo (NL)

Offbeat Music Blog: Jonathan, you have a huge musical output but by trade you are a scientist.

Shearwater’s Jonathan Meiburg: Well, I jumped off the train of becoming a scientist, basically. I was on my way to it but I stopped my graduate studies to become a full-time musician. It has not ever really left me. Recently I got a contract to writer a book about the birds that I have been interested in for so many years. I have been able to re-engage with some of those interests. I think they feed each other, the music and the research. I think of them as two sides of the same thing: One is like the receiver part and the other is the transmitter part if that makes sense.

OMB: Do you see it as a counterpoint, as in, if you are sick of the science bit, you turn to music or the other way round? Or do you find there is a consensus, even if that consensus is within you?

JM: I would say yes to all of the above. There are times when you get quite tired of things that aren’t fun about doing music or doing science and the other part starts to look more appealing in contrast. Last year I was in Guyana for about six weeks on a remote river; it was such a strange place to me – nothing looked familiar at all. None of the trees, none of the animals. It was like visiting another planet. I felt completely useless and out of my own in the most profound way. which is kind of scary. I remember thinking at the time: “Gosh, I’ll be glad if I have done this rather than to be doing it. But I took a lot of notes and recordings and photographs and didn’t get eaten by a crocodile and came back. I am still digesting that experience. I think, things like that can’t help but inform your artistic brain works, how your musical brain works. Certainly the sound of that place was deeply inspiring. So many kinds of creatures making different sounds, all within their little niche, in their frequency range, so they can hear one another. It makes an orchestra seem not very sophisticated.

OMB: The last interview I did was with Martin Phillipps from The Chills from Dunedin in New Zealand. (JM: Oh yeah, yeah!) who released an album after so many years and went on tour with it, which was very good. He said that at the time they started out, there was a specific Dunedin sound (JM: Yes, there was!), simply because they were so isolated. I remember you saying somewhere if you go to these remote places, if you want to hear music, you have to make it yourself. (JM: You do!) It was very much the same thing Martin said. Importing music was just too expensive, he said, so we had to make it ourselves. However happy he is about all the social media and the digital age all over the globe, he said that thing will be lost, that isolated situation.

JM: Sometimes it seems we invented the internet to destroy culture and sometimes we invented it to preserve it. It sort of does both I think.

OMB: When you write songs, do you think how they would outlast a certain period? (JM: No…) How to make them timeless?

JM: (Laughs). If you could know that, everyone would do it. I just try to make music that I respond to in the hope that I am not completely different from every other person on earth. If there is something in it that moves me, there will be something in it that moves some other person too. Jeff Mangum from Neutral Milk Hotel once said to me: If it’s meaningful to you, whatever it is, it will be meaningful to others like you. So you just have to hope that there others like you.

OMB: Even though it might have a different meaning to them.

JM: Yes, yes, it’s not that it would be the same thing to everyone but there would be some level at which it speaks. Psychiatrists couldn’t keep their jobs if everyone is different (laughs).

OMB: If you look at your albums in a chronological order, there seems to be to me as a person with OCD (JM squeaks) a very nice order punctuated by label changes, also by a development in style and most likely personal changes as well. Could you take as in one-liners through your albums and your intentions or the atmospheres of the albums?

JM: The first one that is really the first Shearwater record that I care for people to hear at all is “Palo Santo” (in fact the fourth Shearwater record – OMB) which was the first one we released on Matador in 2006. I had just come back from research experience in the Galapagos for a couple of months which was a really moving and odd experience because it was just me and two other people on an island. We didn’t see anyone else for a very long time. It does strange things to your mind – I started to think that parts of the island were haunted. I knew that they weren’t but there places that I really didn’t want to go. I could feel sort of mindmapping out the territory: Certain places were special, certain places were to be avoided. I was not expecting that at all to happen. The eeriness of that place came through on that record. Palo Santo is the name of one the trees that grows there. Its sap smells like incense. You walk through a grove of them and it has been heated by the sun and the volcanic lava flows. They are able to sink their roots into what looks like bare rock. And I was obsessed with Nico’s music at the time, so the record is sort of about her. Listening to Chelsea Girls and then listening to The Marble Index, hearing these two records back to back, there is such a difference between them and I wondered what was in that gap and who she really was. So the record is kind of about that.

Rook: I had been reading a lot of the writer Peter Matthiessen at the time and I was thinking more about the natural world and our place in it. It is a more pastoral sounding record, I think. It is not very electric, that record.

The next one is The Golden Archipelago. I think of those three records as a kind of trilogy and that one is sort of the conclusion of it. It begins with the national anthem of Bikini Atoll sung by Bikini islanders which is the most remarkable thing, trying to remember what the English translation of the words of it is. It’s like: No longer can I stay, it’s true. No longer can I lie on my sleeping mat and pillow because of my island and what happened there. My spirit wanders in great distress until it meets with the current of immense power. And only there can I find peace. (OMB: That makes a beautiful change for a national anthem!) That’s the national anthem of this island, it’s unbelievable. So the album is kind of a trip into that anthem in some ways and goes back and forth in time. Some of it references things that happened to my grandfather when he was stationed on Guam in WWII. He was from South Carolina and suddenly found himself in the middle of the South Pacific and running a radio transmitter. That album was probably the most lush of the three, it had the largest orchestral arrangements. It was really hard to play those songs. It is hard to get them translate live in a way that felt satisfying. At the end of that time we played a show where we played all of these three albums together. That kind of marked the end of that time for me and the end of that line-up.

For the following record, Animal Joy…

OBM: Inbetween you also left Matador?

JM: Yeah, we did. I gave Matador the demos for Animal Joy and they didn’t want it. Luckily we had friends at Sub Pop who did want to put it out. So I made that record for them. Animal Joy was a transitional time for me personally. I was in the process of leaving Austin, Texas, where I had lived for twelve years. I was having a really difficult time and so I decided to write about my own life in a way that other people could hopefully still see themselves in or identify with. That record to me is very personal, very much about that time in my life. (OBM: Cathartic?) Yeah, that’s a very good word for it. That song Insolence just feels like breaking down a door and always did every time I played it.

After that we did the Fellow Travellers record which was kind of a way to look back a little bit because it was songs by bands we toured with over the years. Many of those bands also participated in the record but the rule was that they couldn’t play on their own songs so they had to play on someone else’s song. I think that record got misunderstood. Nobody seemed to know what to make of that record but I was very proud of it at the time. We made it in a great hurry., just two or three weeks, the whole thing.

And then we spent almost two years on the recent album Jetplane And Oxbow, on and off, not continuously. It was a long time from beginning to end. I try and have a title and an image first when I start a record because it allows me to find songs that sound like the image looks in a way that they can sort of cohere.

OBM: You do like a coherent album. (JM: I do. I can’t help it.) Almost like a concept album?

JM: Almost but concept album always to me implies that there has to be like a plot or something and that’s a musical to me more or less and I don’t want to write a musical, or Pink Floyd’s The Wall or something. I don’t want that. I just want every song on an album to address a facet of or illuminate a part of the larger picture that the album presents if you listen to the whole thing.

Jetplane And Oxbow is our longest, definitely our loudest record. I wanted to place it sonically in a particular era which is about 1979 or 1980. That was the time when some records that I love came out. And I think it was an interesting time for music because digital technology was just beginning to change it in such a big way. But people didn’t know how it was going to change, so those records are really hybrid creations, a lot of them really, even the darkest ones in a way optimistic in the sense of possibilities stemming from this new technology and the new sounds that could be made and the things that could be done with them. I don’t remember that time (OBM (mutters) I do! JM (laughs)), I was four.

OBM: I think around that time I bought my first Depeche Mode album, them fiddling with the little synthesises, the Vince Clarke era.

JM: Yeah and drum machines and things like that were started to be used but they hadn’t taken over yet. MIDI didn’t exist yet, everything wasn’t timed out to a clock.

OBM: No, it was more a tinkering.

JM: Yes, it hadn’t been established yet and I think there was lot more room for creativity with these devices in some ways. Even though the digital world of sound we now work with is infinitely more flexible…in one way.

But I was listening to an interview with David Bowie from 1981 when Scary Monsters came out. He talked about that record being social protest music to him. I thought that is really interesting. I never thought about that record that way. Then going back and listening to it with that in mind, I thought, I’d really love to make a record like that, that was a protest album but kind of an oblique protest album. That wasn’t hitting you with slogans or telling you what to think because I really don’t like slogans. And that was the record that ultimately think we made. Which of course now unfortunately seems more appropriate than I would like for it to be because the whole world seems to have become crazier since the time we finished that record.

OBM: So it has taken you quite a few years to do it. Are you still happy with Jetplane And Oxbow. Can you still identify with all of the songs?

JM: In all of the records? No, but a lot of them. Some I haven’t returned to in a long time, some did not want to be played somehow and some we never stopped playing. We just started playing Hail Mary again from Palo Santo. I made a band arrangement which I hadn’t done since 2010. So it’s been quite a while since that one came back. And there is another song from Palo Santo which we are probably going to play tonight, haven’t played it in a while. In general you identify with the songs that are most recent, because you are closest to the version of yourself that wrote them. I wrote the songs on Jetplane And Oxbow specifically with performance in mind. And if we were working on a song and it did not seem interesting to perform or watched being performed, we’d stop working on it and change gears. We have been able to play most of the songs on the record on the set and really enjoyed it and audiences seem to have liked it as well.

OBM: You were just after finishing one tour and you are back again. You seem to enjoy life on the road?

JM: (Sighs doubtingly). It is alright.

OBM: Well, maybe some parts of it.

JM (laughs). Some parts aren’t fun, some parts are wonderful. Last night we had a great show in Rotterdam, it was just a great, sweaty, loud rock show. It was wonderful. A few nights before that we played in an opera house in Antwerp that was just this gorgeous, gracious, beautiful space that had a completely different feeling about it. I love that about touring. The place you are playing can bring different energies within your own performance and the songs. But I have a book to write and I need to finish it, (laughs), so after this tour I need to get home and lock myself into a room for a while.

OBM: You are not located in Texas anymore.

JM: No, I have lived in New York for the last five years.

OBM: It kind of shows, you can hear it in the way. Most people would go when hearing you: Naaaw, they are never from Texas. And then one replies: Look, it’s Austin, this is were SXSW is. It’s not the cliché we think of here, you know. Texas is for most of us the US in a nutshell.

JM: Yeah, cowboys and cactuses and insane people with guns. I always tell people, Texas is bigger than you think. People say, Austin is not really Texas. That’s not true. Austin is really Texas. Texas is that also. I actually have a lot of hope for Texas. I think within twenty or thirty years it could be a far different place that’s far more inclusive and interesting than we find it our. There is sort of a reactionary time going politically in parts of the US, partly as the US undergoes a demographic transition which I think is a good thing and completely inevitable. That’s just how I feel about the US in general. There are things I can’t stand about it. Also I still have a lot of hope for it. What’S right about it could still overcome what’s wrong with it. But the record is certainly an exploration of the pathologies that plague our country.

OBM: Possibly not only your country….

JM: Yeah, but I mean people talk about this idea that you can make it on your own in your life in the US which to me just seems absolutely preposterous. But that energy does give people a lot of creative initiative. But it has a dark side too – it can be just merciless. People don’t want to look after other people who are suffering or couldn’t possibly improve their own situation without help. That to me is deeply corrosive and ultimately undoes the things that we think are good about the country. This is part of what I was trying to ponder on the record.

Thank you so much, Jonathan Meiburg!